I first learnt about the Indian caste system while studying history in school. The caste system was formalized in a legal treatise called Manusmriti, dating from about 1,000 B.C. Manusmriti is a code of conduct put together by Brahmins, mainly for themselves, and some other “upper” caste communities. The text defined karma (actions) and dharma (duty) for Hindus, who today represent the majority of India’s population. In it, society was divided into four strictly hierarchical groups known as ‘varnas’ as shown below.

Over time, as social segregation and caste prejudice deepened, another layer of Shudras emerged at the base of the pyramid: Dalits, meaning “divided, split, broken, scattered” in classical Sanskrit. They got their other name — “untouchables” — because their mere touch could supposedly defile. I will refer to them as Bahujans (literally means “people in majority”), referring to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Castes (OBC), along with religious minorities.

But in school, I also learnt about the fight against caste discrimination by great leaders like Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, Jyotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule. And how after a long and difficult journey finally on 26th January 1950, India came under liberal forces as a sovereign, democratic and republic. And for the longest time, I was under the misconception, that this was the end of the age old caste system in India.

Recently, I read a couple of graphic novels depicting the stories of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar (Bhimayana – Experience of untouchability) and The Phules (A gardener in the wasteland). Reading the story of Ambedkar, gave me goosebumps. Even as a child, the kind of discrimination he had to face for basic needs like water was heart wrenching. And he was, what I would call, privileged among the Bahujans as his father worked for the then King of Baroda, resulting in him always having proper clothes to wear and access to education. He got the opportunity to go and study at the Columbia University in America and the London school of Economics which was otherwise extremely rare among their caste.

“In Columbia University, I experienced social equality for the first time.” – Ambedkar in Columbia Alumni News, Dec 1930

In spite of being so highly educated, when he returned back to the city of Baroda in 1917 to serve the state and repay his debt to the Maharaja by working as a probationer in the Accountant Generals office, he could not find any motel that would let him stay. The government offices were also prolonging allocating him official quarters without any rhyme or reason. Even his friends did not welcome him to their house. He had to give up on his obligation to the Maha

raja and run back to Mumbai, just because he was an untouchable.

These books opened my eyes to today’s harsh reality and I started probing around and reading more on prevalence of caste discrimination in the 21st century.

The Ugly truth

Caste is an unfortunate and ugly truth in Indian society. For generations of Indians, the ancient code of social stratification known as the caste system has defined how people earn a living and whom they marry.

Most of us feel that caste is no longer an issue. But that’s not true. Even today in 2020, caste is very much real. 70 years after the caste system was abolished by the constitution, India still practices untouchability. Despite reform efforts, deep-rooted bias and entitlement hold firm among higher castes, while those on the lowest rungs still face marginalization, discrimination and violence.

Here are some of the very few selected recent examples to look at :

You can check out the full article here

And all this violence was just a result of a Dalit like Mr. Sardar speaking out and demanding what is rightfully his. He was beaten up and scalped for insisting on being paid the wages (about 5200Rs ) the higher caste landlord owed his son for working at his rice paddy.

In September 2006, an upper caste mob, according to eyewitnesses, paraded a mother and her 17 year old daughter naked,raped and killed them. Their brothers aged 19 and 21 too were murdered. Their bodies were dumped in a canal. This gruesome incident occurred in Khairlanji, Bhandardara, only 780kms away from Mumbai but too far it appears to muster national outrage.

In June 2017, a groom was threatened for riding a horse to his wedding – because doing so is considered an upper caste privilege. And this is not the first time a Dalit riding a horse to his wedding has been threatened. A similar incident occurred in 2015 when villagers hurled stones at a Dalit groom in the central state of Madhya Pradesh.

In June 2018, three Dalit boys were stripped, beaten and paraded naked by villagers in the western state of Maharashtra last week for swimming in a well that belonged to an upper-caste family, police said.

In October 2011, six Dalit women were gang-raped in a village of the Bhojpur district which has a long history of violence against Bahujans. But the worst part is things are not getting better with time. Even today on 6 April 2020, amid the national lock down, five people belonging to the Dalit community have been injured in Bhojpur district of Bihar after they were fired upon by members of dominant caste groups on Sunday night.

And if you think that untouchability exists only in the villages , that is not true. Not only does caste resist changes by time, it also manages to transcend the rural-urban divide.

Recently in Delhi, three students training for their civil service exams were beaten up and evicted after they were discovered to be Dalit.

You can read the full article here.

A similar incident happened with the sister of my friend from architecture college in Mumbai itself. It took her a long time to be able to rent a room. And after a long search when she finally found a place, it was on the condition that she would never go near the temple in their house.

“Dalits are not allowed to drink from the same wells, attend the same temples, wear shoes in the presence of an upper caste, or drink from the same cups in tea stalls,” said Smita Narula, a senior researcher with Human Rights Watch, and author of Broken People: Caste Violence Against India’s “Untouchables.”

The data collected by the India Human Development Survey conducted by the National Council of Applied Economic Research says-

- More than 160 million people in India are considered ‘Untouchable’

- About 27 percent of the Indian households still practice untouchability

- Since, Brahmins come on the top of the caste chart, 52 percent of them still practice untouchability

- Only 5.34 percent of Indian marriages are inter-caste

- It is most widespread in Madhya Pradesh with 53 percent practicing untouchability. Madhya Pradesh is followed by Himachal Pradesh with 50 per cent. Chhattisgarh comes on the 3rd position with 48 percent, Rajasthan and Bihar with 47 percent, Uttar Pradesh with 43 percent, and Uttarakhand with 40 percent

- The survey also shows that almost every third Hindu practises untouchability (33-35%)

- Every hour two Bahujans are assaulted; every day two Bahujans are murdered, and two Dalit homes are torched.

- Nearly 90 percent of all the poor Indians and 95 percent of all the illiterate Indians are Bahujans, according to figures presented at the International Dalit Conference that took place May 2003 in Vancouver, Canada.

Caste and reservations

For thousands of years, education was denied to the majority of the population of our country on the basis of one’s birth. Seven decades ago, the founders of postcolonial India outlawed caste discrimination in the constitution. Yet caste remains a significant factor in deciding everything from family ties and cultural traditions to educational and economic opportunities, especially in small towns and villages, where more than 70% of Indians live. Nearly a third of Bahujans make less than Rs. 100 a day, and many don’t have access to education or running water. Untouchables perform jobs that are traditionally considered “unclean” or exceedingly menial, and for very little pay. One million Bahujans of a specific sub caste work as manual scavengers, cleaning latrines and sewers by hand and clearing away dead animals. It is estimated that over 600 sewer workers die every year. That is more than 10 times the Indian soldiers killed by terrorists. Millions more are agricultural workers trapped in an inescapable cycle of extreme poverty, illiteracy, and oppression. Very few of them hold office jobs.

“Reservation” is a tool to give education and jobs to the oppressed on the basis of their caste – that very caste on the basis of which they were earlier denied education and jobs.

For many Bahujans education is the only way out of poverty, but that isn’t easy. Many upper caste and privileged people think that these reservations are not fair. They feel that it robs people with merit of opportunities. Even I used to be one of them till few months back when I realized we are so self absorbed that we cannot see the big picture beyond our own selfish needs.

Reservations are not meant to fix caste inequality , but to prevent caste supremacists from outright denying the less privileged their right to learn altogether.

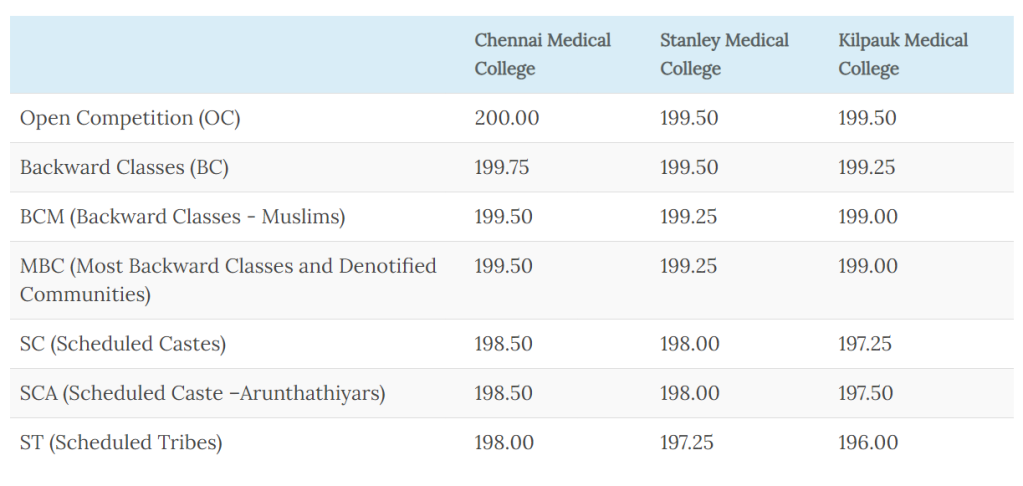

Some people feel that reservations discredit quality and talent. That is a myth. Even the reserved seats ate allotted based on merit. For example:

This table clearly shows there is hardly any difference between the cut off marks between the open category and the reserved seats. It is true that this difference might vary from course to course and college to college but the underlying fact that reservations are like charity and not merit based is false. Also the idea that low caste people are inactive and not interested in education is an upper caste myth where the lower castes are so objectified as unworthy, that the idea that they too study to create careers simply does not occur to the thoughtless flock of upper caste privileged people taught to resent their very presence. If anything these people have to work ten times harder to even try and reach the same stage, overcoming obstacles at every level. Many of them leave their education mid way at an early age itself as they are unable to bear the teasing in the classroom not only by their fellow classmates but many a times also by teachers.

Some people believe reservations should address economic vulnerability and not caste. – Vidyut, who has a keen interest in mass psychology and uses it as a lens to understand contemporary politics, social inequality and other dynamics of power within the country gives a very logical reply to that –

“It is like saying, we will fight one kind of inequality but not another. Removing protections to one kind of vulnerable group in order to assist another is not a better method, it is fundamental inhumanity that refuses to take responsibility for the whole range of assistance needed. Replacing caste based reservations with those that are economic capacity based will have an extremely predictable result of filling seats with high caste poor people and disenfranchising the lower castes while pretending that this is a more just system. Poverty, on the other hand, does not necessarily need reservations, but assistance. Lack of economic resources can be fixed with free tuition and funds to enable study.”

It is true that a few rich lower caste people are benefited by these reservations. But isn’t that true with everyone and everything in this society? All educational institutes have management seats for privileged people who get in just by giving huge donations. Also don’t Bahujans deserve some concession for the generations of their ancestors being ill treated. “Also, in order to try and control this phenomenon, a logical move would be to put a rule that goes “people richer than XYZ must seek admissions through the general quota” and not occupy seats meant to protect the deprived. But that will not happen, because the last thing they want is for more competition in their “merit”. They’d rather point out to the privileged few and use it as an excuse to deny all. – she adds.

To conclude, whether we like it or not, it is a fact that our society is divided into groups based on castes. Reservations were introduced to end the dominance of certain groups and give the neglected and oppressed groups a push so that they could become equal to the other groups and hold a respectable place in the society. In an Utopian India, where caste discrimination has been truly abolished in all its forms, there will be no need of reservations. But not before that.

Caste and political representation

Enforcement of laws related to caste discrimination would be stringent if more people of this background are a part of our governance system. To allow for proportional representation in certain state and federal institutions, the constitution reserves 22.5 percent of federal government jobs, seats in state legislatures, the lower house of parliament, and educational institutions for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. The reservation policy, however, has not been fully implemented. The National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes’ (1996-1997 and 1997-1998) report indicates that of the total scheduled caste reservation quota in the Central Government, 54 percent remains unfilled. More than 88 percent of posts reserved in the public sector remain unfilled as do 45 percent in state banks. A closer examination of the caste composition of government services, institutions of education and other services, however, reveals that even though Brahmin’s represented only 5 percent of the population in 1989, they comprised 70 percent of the Class I officers in governmental services. At universities, upper-castes occupy 90 percent of the teaching posts in the social sciences and 94 percent in the sciences, while Dalit representation is only 1.2 and 0.5 percent, respectively.

During elections, already under the thumb of local landlords and police officials,

Dalit villagers who do not comply to voting for certain candidates have been harassed, beaten, and murdered. Bahujans who have contested political office in village councils and municipalities through seats that have been constitutionally “reserved” for them have been threatened with physical abuse and even death in order to get them to withdraw from the campaign. In the village of Melavalavu, in Tamil Nadu’s Madurai district, following the election of a Dalit to the village council presidency, members of a higher-caste group murdered six Bhaujans in June 1997, including the elected council president, whom they beheaded.

Caste and marriage

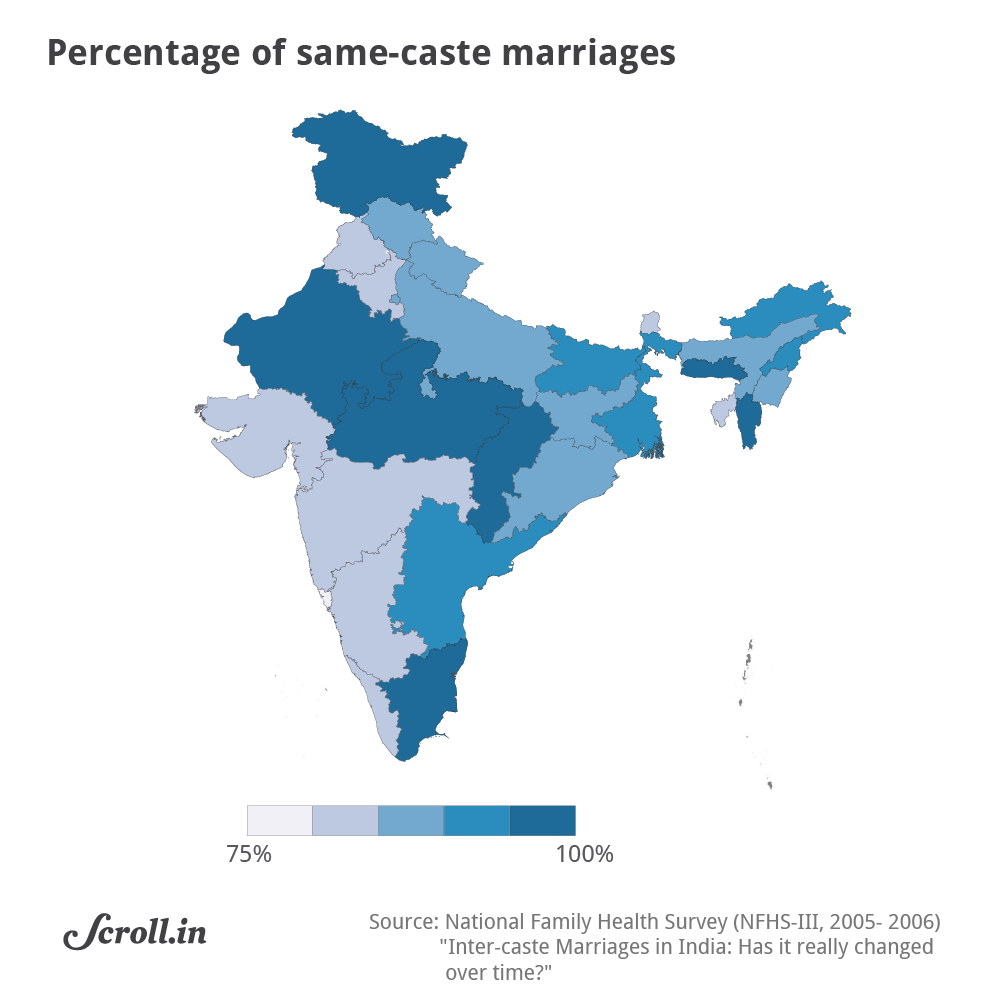

Marriages within the caste is the norm of the Indian society. To think of marriages between castes is a difficult and socially unacceptable proposition. Even today, the custom of marrying only within the caste, known as endogamy, has not changed and inter caste marriages are frowned upon. In 2011, the rate of inter-caste marriages in India was as low as 5.8%.

The condemnation can be quite severe, ranging from social ostracism to punitive violence. On August 6, 2001, in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, an upper-caste Brahmin boy and a lower-caste Jat girl were dragged to the roof of a house and publicly hanged by members of their own families as hundreds of spectators looked on as a punishment for refusing to end an inter-caste relationship.

Shockingly, urban households do not have a higher probability of inter-caste marriage than rural households. Ironically, metropolitan cities have the lowest rate among urban areas. Based on NFHS 2006-07, caste endogamy is also unaffected by how developed or industrialized a particular state is, even though Indian states differ widely in this aspect. Tamil Nadu, while relatively industrialized, has a caste endogamy rate of 97% while underdeveloped Odisha’s is 88%.

Resistance and progress

India needs to break the shackles of prejudice, discrimination and violence that keep more than one-quarter of India’s population at the bottom of socio-economic hierarchy and targets of hate crimes if it one day aims at becoming a global superpower. Today, grassroots efforts to change are emerging, despite retaliation and intimidation by local officials and upper-caste people. There is a growing movement of activists, trade unions, and other NGOs that are organizing to democratically and peacefully demand their rights, higher wages, and more equitable land distribution. In the wake of the COVID 19 pandemic, its the first time there is an active recognition of the people who are doing the work that society’s hygiene rests on. A group of concerned citizens – academics, rights activists and others – have written an open letter to all minister in the Central and state governments, as well as society at large, to highlight the plight of sanitation workers and list measures that can be taken for their welfare which includes ensuring they are classified as health workers and paid a minimum wage of at least Rs 20,000 per month along with a proper health insurance and allowance covered under the description of ‘hazardous works’.

Caste discrimination is like a disease in our society. And like any other disease we need to eradicate it from the country. We need to monitor the cases of caste violence and treat them with justice and social reform. When we reach a point where humanity has won and caste discrimination has ended we can remove the reservations which are like “vaccines”. You wouldn’t stop vaccinating the population before a dangerous disease is eradicated, right?

Vidyut added

Remember, each one of us play an important role in keeping this discrimination alive in our country. If all of us start changing our own thoughts and behavior, educate others and bring this grave issue to a limelight, we could slowly bring this inhumane discrimination to an end.

References:

https://www.bloomberg.com/quicktake/india-s-caste-system

https://aamjanata.com/democracy/10-things-to-remember-when-discussing-caste-reservations/

https://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/globalcaste/caste0801-03.htm

Why caste-based reservation is a logical social-justice measure

https://homegrown.co.in/article/18426/untouchability-is-still-widely-practised-in-india-says-recent-caste-survey-findings